Two complementary studies reveal how an insufficient supply of energy in macrophages, key immune cells in artery walls, drives the progression of atherosclerosis — and how this knowledge could lead to better diagnostics and future therapies. The University of Eastern Finland was centrally involved in both studies.

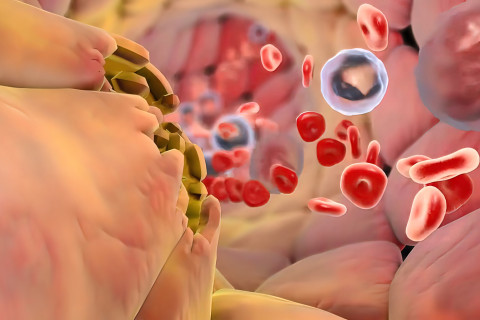

Atherosclerosis — the buildup of fatty plaques inside arteries — is the leading cause of heart attacks and strokes worldwide. Although the role of cholesterol in plaque formation has long been a central focus, scientists increasingly recognise that the immune system plays a decisive role in determining whether plaques remain stable or become unstable and thus prone to rupture, which can lead to heart attacks or strokes.

In two newly published studies, an international team of researchers showed that poor availability of the amino acid glutamine in macrophages can determine the worsening of artery plaques. The researchers also identified new ways to detect dangerous plaques.

Immune cells need fuel to repair damaged arteries

Macrophages are the body’s clean-up crew. Inside artery plaques, they ingest fats, remove dying cells, and help repair damaged tissue. But to perform these protective tasks, macrophages require energy.

In the first study, published in Nature Metabolism, the researchers discovered that macrophages rely heavily on glutamine uptake from their environment to fuel their restorative functions. A specific transporter protein, SLC7A7, acts as a gateway that allows glutamine to enter the cell. When this gateway is blocked, macrophages lose energy and perform poorly, resulting in plaques that are larger and more unstable, which is a known risk factor for heart attacks and strokes in people.

Reduced activity of this pathway was linked to more dangerous plaque features also in human artery samples.

“These findings suggest that restoring or supporting macrophage metabolism could one day help stabilise plaques and prevent heart attacks or strokes,” says Professor Minna Kaikkonen-Määttä from the University of Eastern Finland.

New tools to identify high-risk plaques

The second study, published in Cardiovascular Research, builds on this biological insight and moves toward the clinic. By studying macrophages with advanced single-cell technologies, the researchers identified protein markers such as TREM2, FOLR2, and SLC7A7 that highlight high-risk plaques.

Based on these markers, PET imaging could be used to detect inflammatory plaque activity rather than just the size of the plaques.

The researchers also found that soluble TREM2 in blood may help distinguish between stable and symptomatic plaques, raising the possibility of a future blood test to identify patients at highest risk.

The research reflects close international collaboration, with the University of Barcelona contributing to both studies, among others. The first study was led by Université Côte d’Azur, while the second was co-led by the University of Turku.

Research articles:

Benhmammouch, S. et al. Slc7a7 licenses macrophage glutaminolysis for restorative functions in atherosclerosis. Nat Metab 7, 1924–1938 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-025-01354-2

Örd T. et al. Single-cell to pre-clinical evaluation of Trem2, Folr2, and Slc7a7 as macrophage-associated biomarkers for atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2025 Dec 18;121(16):2503-2519. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaf210. PMID: 41206594. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/41206594/